Description

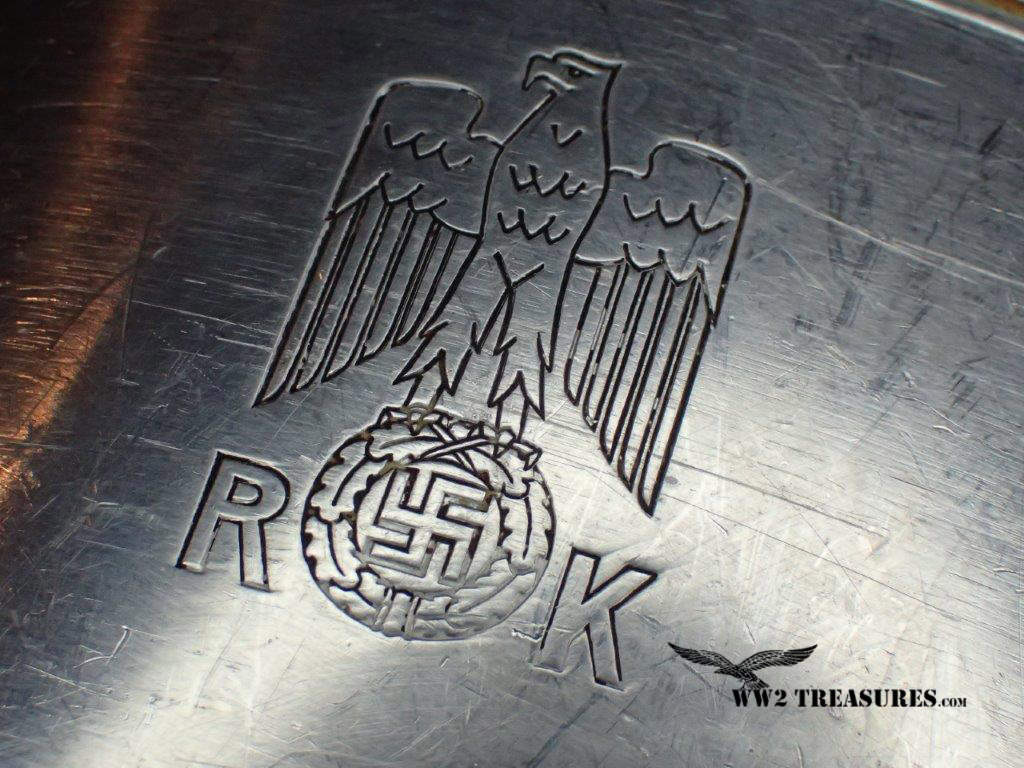

Here’s an extremely rare Reich Chancellery Sauce Pan made by WMF. It is roll stamped with the party eagle clutching an oak wreath with a swastika. The “R” and “K” flank the sides of the wreath. In addition, the maker mark and cookware line “WMF Cromargan” is stamped to the right of the handle. It is made of stainless steel and chrome with a heavy cast iron base inlay. It’s a very stout quality made pan weighing in at 10 1/2 pounds. It measures 22 1/2″ long from handle to handle and the pans diameter is 10 1/2″ by 5 1/2″ deep. Reich Chancellery artifacts like this pan are extremely rare.

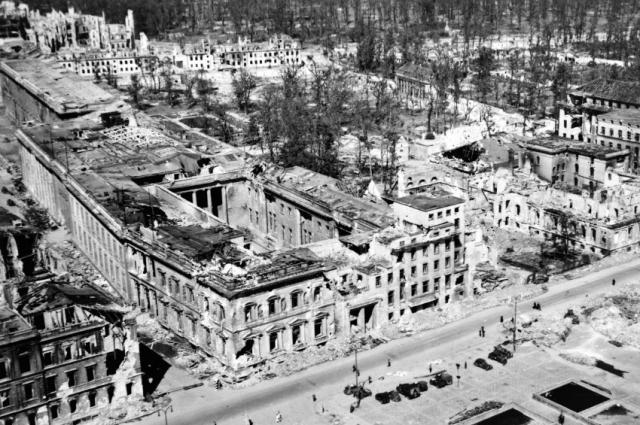

The Reich Chancellery was Hitler’s official residence, office and bunker; from here he planned the war and here it ended with his death.

Any Chancellery item is extremely rare because the complex was badly damaged during the Battle of Berlin in April 1945. It was almost destroyed. Only walls remained, riddled by countless shrapnel, yawning by big shot-holes from shells. Ceilings survived only partially. The last defense took place inside the Chancellery. After World War II ended, the remains were demolished by orders of the Soviet occupation forces. I would imagine the veteran who brought this item home had to barter with the Russians to obtain it.

WMF History – Major Supplier to the Military in 1914

The acquisition of another competitor–Göppingen-based Schauffler & Safft–in 1897 marked a new chapter in WMF’s history. The company was founded in 1876 by two former employees of a Göppingen tinware factory, Hans Schauffler and Adolf Safft, and was the leading German manufacturer of nickel-plated metal goods such as cooking utensils, tea and milk urns, lanterns, tabletop stoves, and, later, coffee makers. Due to Hans Schauffler’s exquisite sales skills, the company exported roughly half of their output. Nickel-plated items, which did not tarnish and were easier to clean, represented serious competition for WMF’s silver-plated products. They could be polished by machines and therefore be made comparatively cheaply.

Less than one year after the takeover, WMF’s supervisory board replaced Carl Haegele with Hans Schauffler as the company’s new executive director. Schauffler focused on boosting sales, and within seven years revenues from the so-called “Göppingen ware” doubled, while the factory’s workforce rose from roughly 500 to almost 1150. However, Schauffler’s sudden death in 1904 left WMF without a leader. The supervisory board decided to establish a board of five directors, each of them with a clearly defined area of responsibility. In 1905, WMF bought another competitor, Cologne-based Orivit AG, a manufacturer of stylish metal tableware and decorative articles which were covered with a layer of brass, bronze, silver, or gold. WMF had paid a significant sum for Orivit. Nevertheless, the company’s efforts to transform the financially struggling firm into a profitable operation eventually failed.

By 1914, WMF had become a leading supplier of silver-plated household items and the largest employer in the state of Wurttemberg. About 4,000 people worked for WMF in Geislingen and another 2,000 worked at other locations in Germany and abroad. There were more than 25 WMF sales outlets in Germany and cutlery accounted for roughly one-fifth of their sales.

The outbreak of World War I in the summer of 1914 brought WMF’s first period of extensive growth to a sudden halt. Metal was a crucial ingredient for the German war economy and not available any longer for civil uses. Exports were halted. WMF’s production in Warsaw was shut down and later sold. In addition, 760 WMF employees were called up by the military. In order to avoid the company’s shutdown, WMF became a major contractor for the German army. Because of its patented process for making cartridges and shells from high-quality steel, the company became almost the sole supplier of these munitions during the war. An increasing number of female employees replaced the men drafted into the army. At its wartime peak, WMF employed about 8,000 workers and put out a total of roughly 200 million bullets and shells for the infantry. Meanwhile, the company’s retail outlets sold products made by other firms.

Economic and Political Turmoil: 1919-45

The decade that followed World War I gave WMF only a short time for recovery between two severe economic downturns. The 1920s started out with two years of accelerating inflation, resulting in the financial ruin of the German middle class. When WMF tried to cut personnel cost by extending work hours in spring 1922, while the wages paid were not sufficient to cover the cost of daily living, a part of the company’s workforce went on a three-month strike.

Despite the economic turmoil, WMF tried to stay on the leading edge of product design and quality for household consumer goods made from metal. Since the demand for decorative items declined due to widespread economic hardship, the company focused on cutlery, serving dishes and kitchenware such as metal graters, colanders, pots, casseroles, and frying pans. In 1920, WMF introduced a new line of cookware made from high-quality steel, which was called “Silit Steel.” Seven years later, WMF launched three product innovations: the company’s first “Siko” pressure cooker, WMF’s first electric coffee maker for commercial use with two different brewing functions, and a non-rusting, acid-resistant, and “taste-free” pan made from Krupp’s V2A stainless steel with a high chrome content. Soon after, a whole new line of this type of cookware was launched under the brand name “Cromargan.”

In 1924, WMF’s patent for its special silver-plating process for cutlery expired. Although many competitors immediately adopted the technology, WMF managed to expand its cutlery business. In 1926, the company started making solid silver cutlery. By 1928, cutlery sales accounted for roughly two-thirds of WMF’s total revenues. In 1932, the company introduced a line of Cromargan cutlery.

The worldwide economic depression that was initiated by the New York Stock Exchange crash in late October 1929 reached Germany in the early 1930s. WMF’s exports–which accounted for about one-third of the company’s revenues–dropped by 67 percent between 1930 and 1933. Although WMF shut down all production plants except the one in Geislingen and laid off hundreds of workers, the company still found itself in the red for the first time. The National Socialist (Nazi) Party that came into power in 1933 launched a massive government-financed program designed to lift the nation out of the depression, resulting in a short period of recovery for WMF. While exports were down, the company greatly expanded its domestic network of sales outlets to 141 by the end of the 1930s. While the Nazi government’s economic policy initially was a success, it soon became apparent that it had another agenda. In 1936, the leader of the National Socialist Party, Adolf Hitler, demanded that the German economy had to be ready for another war within four years.

In order to continue operations after World War I, WMF had certified to the Allied Control Commission that all the machinery that was used to produce ammunition had been sold or destroyed and that in the future WMF would not make any more war goods. However, immediately after Hitler’s call for rearmament, WMF’s executive director Hugo Debach once more set the course to become a military contractor. Two months after the beginning of World War II, in December 1939, he suddenly died.

Before and during the war, WMF struggled with increasingly severe shortages of raw material. Once again, the company became a major supplier of ammunition and manufactured parts for airplanes. Beginning in 1940 a growing number of prisoners of war–and later forced laborers–were employed by WMF. These workers, about half of whom came from the Soviet Union, lived in camps around Geislingen and accounted for about one-third of the company’s total workforce by mid-1944. Beginning in February 1944, a separate concentration camp was established by WMF in Geislingen for hundreds of Jewish women from Hungary who were originally destined to die in Auschwitz. As the war came close to the end in April 1945, over 900 female concentration camp prisoners were set free by the American Forces that occupied Geislingen.