Description

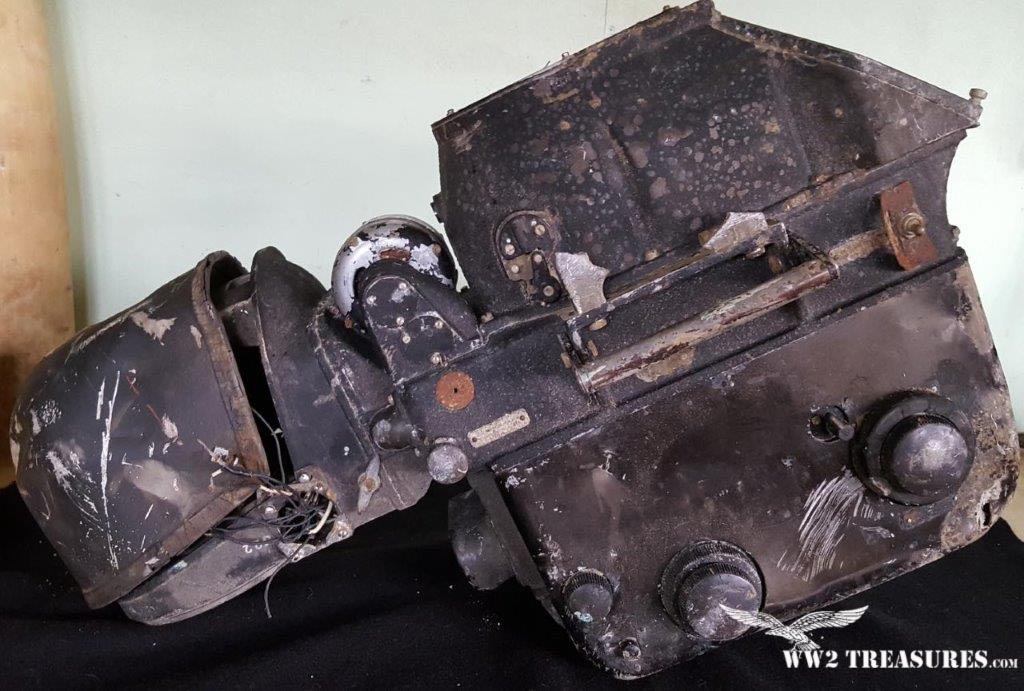

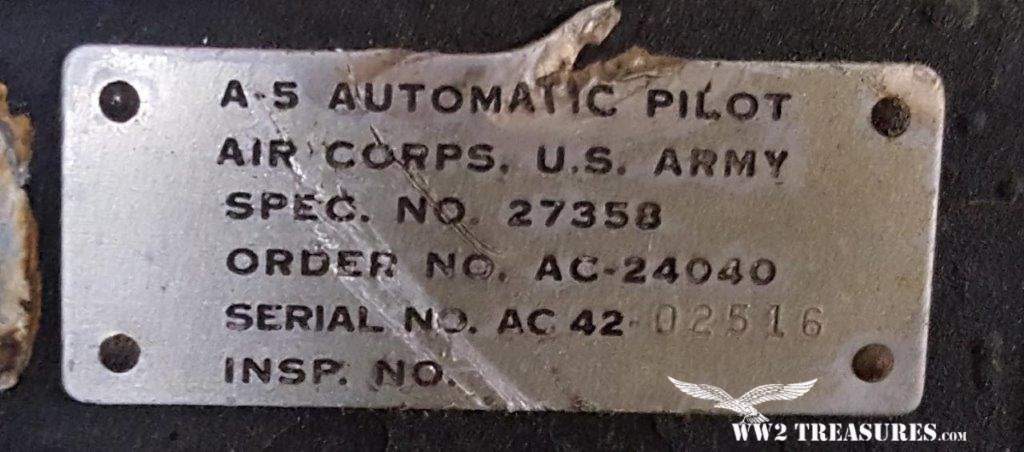

Here’s a B-24 Liberator Sperry Bombsight (with the autopilot unit still attached) from a well documented aircraft #42-7638. The Sperry S-1 bombsight was developed in the 1930’s and was the first bombsight used in the B-24 liberators. It’s purported that the Sperry bombsights were superior to the Norden system, but politics were involved when the government awarded the bombsight contract to Norden in late 1943. As you can see by the illustrations, these bombsights are packed with precision gears & controls and are very heavy.

The excavation of this particular B-24 was featured in a 1975 documentary “Some Of Our Airmen Are No Longer Missing” (https://youtu.be/gTpAXE4WIJM). The details of the excavation starts around the 19:00 min mark. There is a copious amount of documentation on this aircraft. For serious collectors, it doesn’t get any better than this.

Other pieces of this aircraft can be found in a permanent exhibition in The National Museum of the US Airforce in Dayton, Ohio.

This B-24 Liberator, nicknamed Big Banner, was piloted by Capt. Kent Miller and went on it’s final bombing mission on December 22, 1943. It set out from an airbase at Shipdham, England and headed to Munster, Germany where it successfully emptied its payload. It was hit by flak on route back to Shipdham. The Big Banner was ditched in Lake IJsselmeer, Netherlands where it rested until its excavation in August of 1975. All crew members perished with the exception of the co-pilot Charles E. Taylor.

Flight Crew:

| Date 1943 Dec22/22 | A/C Type: B-24 H Liberator

Nick Name: Big Banner |

SN: 42-7638 | |||

| File: 148 | Airforce: USAAF | Sqn/Unit: 44 BG – 66 BS | |||

| 1 | Pilot | F/O Kent F. Miller MIA | |||

| 2 | Co-pilot | 2Lt. Charles E. Taylor rescued by German boat | |||

| 3 | Nav. | 2Lt. Frank A. Passavant MIA | |||

| 4 | B | 2Lt. Donald E. Schaffer MIA | |||

| 5 | RO | T/Sgt James C. Childers MIA | |||

| 6 | BTG | S/Sgt. Stanley Pilch Jr. MIA | |||

| 7 | E | S/Sgt Edward E. Birge fished up, Bunschoten (BU25) | |||

| 8 | LWG | S/Sgt John H. Larson German boat, buried Kampen | |||

| 9 | RWG | S/Sgt Gerald D. McCord w.a. Volendam | |||

| 10 | TG | S/Sgt William J. Sheehan fished up, Urk. | |||

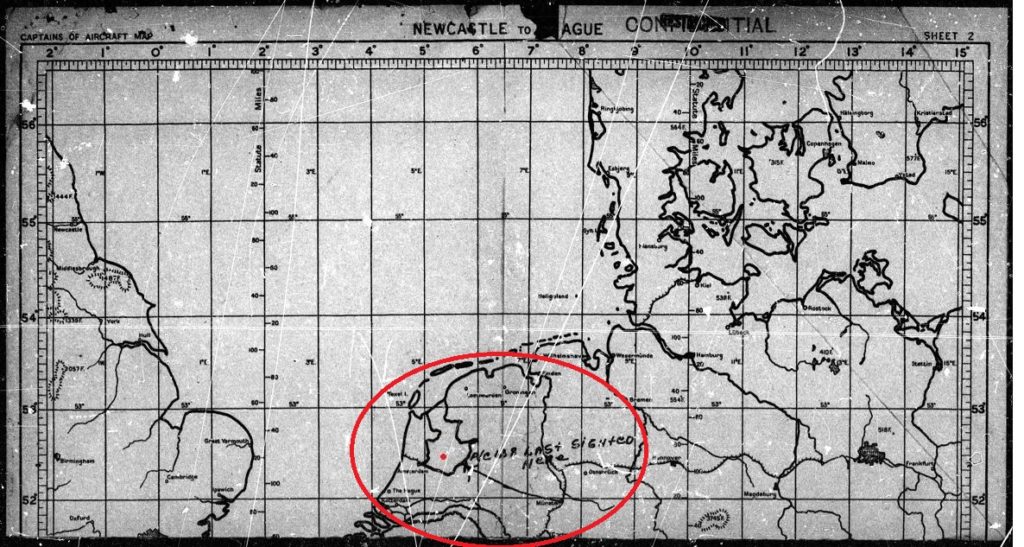

Original Crash Location Map:

Actual Crash Site (water levels were lowered by the dyke system exposing the aircraft) :

Below are the details from the Roll of Honor:

22 December 1943

Munster, Germany

The weather on this mission was terrible, with heavy clouds up above 20,000 feet and thunderstorms as well as very low clouds over Holland. Bombing was done by PFF, with results unobserved. Flak was moderate but accurate, and the 44th BG lost two planes, both from the 66th Squadron.

#42-7638 began lagging behind in the rear of the formation just after the target, tying in with aircraft #42-7533. It was variously reported as being seen lagging behind the formation up to 1437 hours. Each observation was that it was in apparent good condition, but was losing altitude and getting farther behind. At 1437 hour, it was last seen as it dropped beneath the clouds. At that time no chutes had been seen, and since the ship was apparently in “good” condition and under control, it is believed the crew had a good chance to bail out near the German border with Holland. The MACR was correct as Miller and Taylor, the pilots, managed to get as far as the Zuyder Zee, approximately 25 kilometers northeast of Amsterdam, where they were still in heavy clouds but could go no further. Miller gave the bail out signal and some crew members did bail out but the bail out order was changed to ditching as soon as Miller learned they were over water. F/O Miller must have been stunned by the ditching as he did not leave the wreckage. Charles Taylor, the co-pilot, was the only man to survive, although he did get a life raft free of the plane and could see one or two other crewmen in the water near him supported by their Mae Wests. But by the time Taylor got the raft inflated, he did not have the strength left to help them or even to climb inside. He held on until he was rescued. Sgt. Birge, engineer, apparently was trapped by his top turret. Sgt. Pilch got out of the plane, into the water, but must have passed out from shock and the cold water. Larson was seriously wounded, and when the Germans pulled him out of the water, he did not respond to artificial respiration.

Note: The material below has been added. Not all of the details align perfectly, specifically around the point of whether any of the remaining crewmen were able to get out of the ditched B-24, but both accounts are included here for the record.

The co-pilot, Charles E. Taylor, wrote the following: “On December 22, 1943, our group bombed Muenster, Germany. We were flying on Oakley’s wing, and after leaving the target realized we were both losing the formation. Flak had damaged three of our engines and when we realized we would never make it back to England, Miller gave the order to bail out. Four of the crew did bail out in the rear, but when we opened the bomb bay doors, there was a break in the clouds and we saw we were over water, so the order was changed to prepare for ditching, which six of us did. “We hit the water at over 100-mph and submerged immediately. When I released my seat belt, I floated free of the plane. No one else appeared in the water, which I have never understood! I swam around for a few minutes, thinking the plane would sink, but it never did, so I released one of the dinghies, which floated away from me. I caught up with it, but with my wet winter flying suit, flak jacket and Mae West on, I could not climb into it, but just put my arm over the side and passed out. “Obviously, it was not long before a German patrol boat picked me up or I would have died from hypothermia within 15 or 20 minutes, I am quite sure. I was taken to a jail in Amsterdam, awaiting transfer to Frankfurt for interrogation, when I saw that Doug Powers, from Oakley’s crew was also there. We chatted for a few moments, until the Germans broke it up. After interrogation, we were sent to Stalag Luft. “The war in Europe ended on May 8th and on May 13th we were flown to France in B-17s. In June we sailed home, and in September I was ‘separated’ from the service. The next month I went back to my old job with AT&T Long Lines Department. “Thirty years later [in 1975], the Westfield police called me and informed me that the Royal Dutch Air Force had found my plane, after draining a large area of the Zuyder Zee. My wife and I were invited over to Holland to take part in a TV documentary NCRV was planning to make. They eventually recovered the remains of the five missing crewmembers, and sent them back to their families for burial.

Note: The five crew members whose bodies were recovered in the plane were Childers, Miller, Passavant, Pilch, and Shaffer.

“It took the Dutch over four months and many dollars and manpower to accomplish that feat, but they were and are still very grateful for our entry into the war which released them from German occupation. As a matter of fact, they still conduct an annual memorial service at Gronkin, on that reclaimed land, in memory of all airmen who perished on their behalf.”

More can be seen about this aircraft on http://www.zzairwar.nl/dossiers/148.html